What to consider before the lawsuit

Resolution Urgency

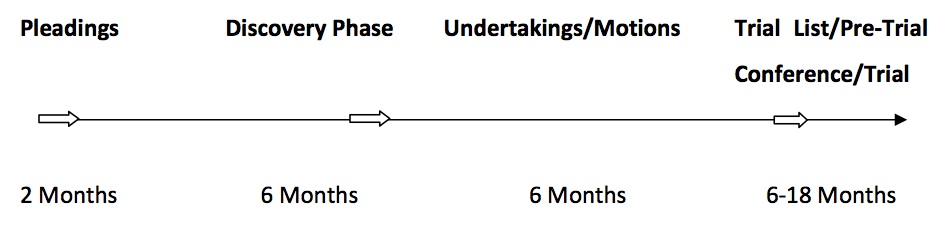

If you are considering starting a lawsuit, you need to be aware that resolving a matter through the courts can be very costly and sometimes take years to obtain a final judgment. Below is an approximate timeline for a straight forward contractual dispute involving only two parties. It assumes things have gone relatively smoothly, with no more than one motion to resolve some issue (i.e. undertakings) and that the ultimate trial will last 1 week and require no expert witnesses or demonstrative evidence:

Consequently, if you are requiring immediate payment, it may be advisable to negotiate with the opposing party to come to a settlement and avoid such a lengthy process. To determine if pursuing a court action is in your best interest or for assistance with alternate dispute resolution options, we encourage you to consult with one of our experienced civil litigators.

Time Limitations

Prior to commencing a legal proceeding, it is critical to ensure that the claim or notice of action is made before the expiration of the limitation period for the legal issue in question. While the Limitations Act, 2002, creates a basic two-year limitation period for most causes of action in Ontario and an ultimate limitation period of fifteen years, these rules are not absolute. For example, the two year limitation runs from the time a person first becomes aware, or ought to have known, he or she has a potential claim. It is important to consult with a lawyer as soon as you think you may have a legal claim to ensure that your matter is not statutorily barred.

Who can sue and be sued?

When a party to be involved in litigation is under a disability, deceased or is a partnership or corporation, identifying the appropriate party is an important consideration. A person is considered under legal "disability", and therefore unable to sue or be sued, if:

- an individual is a minor (under the age of 18 years of age),

- an absentee under the meaning of the Absentees Act, or

- a person is mentally incapable to retain and instruct legal counsel.

With the exception of respondents in applications under the Substitution Decision Act, 1992, proceedings involving a person under legal disability must be commenced, continued, or defended by a litigation guardian unless the court orders or a statute provides otherwise. A minor's parent or another relative often acts as a litigation guardian, however, where the parent or relative was involved in the incident in question it may not be possible to act due to a possible conflict of interest.

The litigation guardian must ensure that the interests of the party under disability are protected and, accordingly, take all steps necessary to achieve this obligation. The law requires that a litigation guardian other than the Children's Lawyer or the Public Guardian and Trustee be represented by a lawyer and cannot act in person.

When dealing with claims regarding a deceased party, as a general rule, a proceeding may be brought by or against an Estate Trustee as representative of an estate or trust and its beneficiaries, without joining the beneficiaries themselves as parties. However, there are instances where it would be inappropriate for the representatives alone to be parties and the beneficiaries must be joined. Should there not be an appointed Estate Trustee, the court may appoint a representative for the estate where it appears that the estate has an interest in, or may be affected by, a legal proceeding.

In those instances where a partnership is to become a party to a civil action, a choice needs to be made as to whether the action should be brought against the partnership itself or the partners individually. One exception to this is where the plaintiff to the claim believes that the individual partners owed a duty to the plaintiff over and above that of the partnership. In most cases, it would generally be more advantageous to bring the action against the partnership. One advantage in particular is that if the composition of the partners change, the action against the partnership can still continue.

Those parties bringing actions against a corporation, compared to those against partnerships, have no choice as to which party to name in the suit. The corporation itself must be named. However, care must be taken to ensure that the cause of action is with the corporation and not with an individual stakeholder in the corporation, such as a director or shareholder. Where the corporation is to be the plaintiff in a lawsuit, its directors have the ability to bring the action on the corporation's behalf. A corporation must normally be represented by a lawyer in a legal proceeding unless the court orders otherwise.

Where to Start Proceedings

Prior to launching an action, it is necessary to determine which court has jurisdiction over the issue in question. If you have a monetary claim for $25,000 or less, in Ontario the action must be started in the Small Claims Court. Those claims for more than $25,000 or claims involving certain non-monetary types of relief should be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

Should your claim meet the $25,000 threshold to be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, there are two different procedures that may be applicable depending upon the value of your claim. If your claim is valued between $25,000 and $100,000, it is started under the Simplified Procedure Rule in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. While claims of over $100,000 can be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice under the ordinary Rules of Civil Procedure, it is not mandatory. Parties can agree to use the simplified procedure for claims over $100,000.

An additional consideration is whether your claim raises any constitutional or federal issues to determine the applicability of any federal law. In general, however, provincial courts do have the jurisdiction necessary to hear many cases involving breaches of federal statutes.

Where to Start Proceedings

Prior to launching an action, it is necessary to determine which court has jurisdiction over the issue in question. If you have a monetary claim for $25,000 or less, in Ontario the action must be started in the Small Claims Court. Those claims for more than $25,000 or claims involving certain non-monetary types of relief should be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

Should your claim meet the $25,000 threshold to be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, there are two different procedures that may be applicable depending upon the value of your claim. If your claim is valued between $25,000 and $100,000, it is started under the Simplified Procedure Rule in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice. While claims of over $100,000 can be started in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice under the ordinary Rules of Civil Procedure, it is not mandatory. Parties can agree to use the simplified procedure for claims over $100,000.

An additional consideration is whether your claim raises any constitutional or federal issues to determine the applicability of any federal law. In general, however, provincial courts do have the jurisdiction necessary to hear many cases involving breaches of federal statutes.

Action v. Application

Should the Superior Court of Justice be the appropriate venue to hear your dispute, it is important to note that there are two different types of proceedings that can be started: Actions and Applications.

An Action is a stereotypical lawsuit, in which an award of money for damages (usually arising from a breach of contract or an injury sustained by, or wrong done onto, another) is the remedy being sought by the person who starts the proceeding. The party who starts the Action is called the "Plaintiff" and the party who is being sued is the "Defendant". The final court ruling (termed a "Judgment") comes after a trial, where witnesses give oral testimony and are subject to cross-examination in open court. A jury or judge may decide the facts which lead to the Judgment, depending on whether or not a "jury notice" was filed.

The other type of proceeding, an Application, is usually commenced to obtain some sort of remedy other than money damages, such as an Order determining or declaring what the rights or obligations of the parties are in a given situation, issues arising from estate disputes, injunctions, possession or control of property, etc. Money issues may be an integral part of an Application. The person starting the Application is termed the "Applicant" and the opposing party is the "Respondent." Evidence is presented by way of sworn affidavits which are filed with the court, rather than oral testimony. These affidavits often have documents attached as "Exhibits", and a person who makes such an affidavit may also be cross-examined on it, before a court reporter. The final court ruling comes after the Application is argued before a judge on the basis of the written documents before the court, including affidavits, exhibits and transcripts of the cross-examinations.

Costs

A fundamental consideration in determining whether or not to pursue or defend a claim is the costs involved. In the traditional sense, "costs" refers to the expenses of a legal proceeding that are paid by each party to his or her own lawyer. These consist of fees for the time spent by the lawyer and his or her support staff working on the case, plus any out-of-pocket disbursements (i.e. court filing fees, service of documents, court reporters, expenses paid for expert reports, etc.), plus HST. While the winning party may be able to receive some of these costs back from the opposing party, in most cases the winning party will still have to pay a portion of their own legal costs.

On top of these fees that will be paid, should the Defendant lose, not only would the Defendant be required to pay any damages ordered by the court, but interest on the damages. Unless expressly stipulated in a contract, the Courts of Justice Act provides for two different interest rates that are applied to civil matters – pre-judgment and post-judgment interest. These interest rates can vary depending upon what the Bank of Canada rate was when the proceeding was commenced. Pre-judgment interest starts from the date the cause of the claim arose until the time of the judgment. After a court judgment is made, post-judgment interest accumulates until the judgment is finally paid. Given that the process to get to final judgment can take several years, interest often becomes an important consideration in settling matters as it can accumulate to a significant sum.

Due to the costs involved, it may be in the parties' best interests to try to work out a settlement. Should negotiations fail and the matter proceed to a trial, the judge will favour the party who offered a settlement that was equal to or greater than the judgment in ordering "substantial indemnity costs" against the opposing party. Substantial indemnity costs are equal to most or all of the successful party's legal costs. Where no offers to settle have been made, the general rule is that only "partial indemnity costs" will be awarded. Partial indemnity costs may cover roughly half or 60% of the actual costs of the successful party.

If you win, can you successfully enforce the judgment?

Unfortunately, just because a court has granted you a judgment or order, does not necessarily mean that a successful party can realize upon that judgment or order. Individuals who have money awards made against them may subsequently go bankrupt or may have sheltered their assets in ways that prevent them from being seized. Certain types of assets, such as pension plans or segregated funds held with life insurance companies, are exempt from seizure under a judgment. Similarly, court orders and injunctions to do (or desist from doing) certain things are occasionally ignored.

Various mechanisms are available to deal with these issues, and to trace assets and seize them, including examination in aid of execution, seizure and sale, fraudulent conveyance statutes, etc. The reality, however, is that these remedies are expensive and time consuming to use and unless there is a strong likelihood of success, it can be a case of throwing good money after bad. For that reason, a less than ideal settlement with guaranteed payment can be a lot more useful than a court judgment awarding everything you want, which is not enforceable. This is an important consideration for parties to keep in mind when assessing their alternatives to a settlement.